Peer Gynt

Act V

Scene 1

Table of Contents

Catalogue of Titles

Logos Virtual Library

Catalogue

Peer Gynt

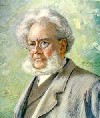

Translated by Robert Farquharson Sharp

Act V

Scene 1

(On board a ship on the North Sea, off the Norwegian coast. Sunset. Stormy weather.)

(Peer Gynt, a vigorous old man, with grizzled hair and beard, is standing aft on the poop. He is dressed half sailor-fashion, with a pea-jacket and long boots. His clothing is rather the worse for wear; he himself is weather-beaten, and has a somewhat harder expression. The captain is standing beside the steersman at the wheel. The crew are forward.)

PEER GYNT (leans with his arms on the bulwark, and gazes towards the land). Look at Hallingskarv in his winter furs;—he’s ruffling it, old one, in the evening glow. The Jokel, his brother, stands behind him askew; he’s got his green ice-mantle still on his back. The Flogefann, now, she is mighty fine,—lying there like a maiden in spotless white. Don’t you be madcaps, old boys that you are! Stand where you stand; you’re but granite knobs.

THE CAPTAIN (shouts forward). Two hands to the wheel, and the lantern aloft!

PEER. It’s blowing up stiff—

THE CAPTAIN. —for a gale to-night.

PEER. Can one see the Ronde Hills from the sea?

THE CAPTAIN. No, how should you? They lie at the back of the snow-fields.

PEER. Or Blaho?

THE CAPTAIN. No; but from up in the rigging, you’ve a glimpse, in clear weather, of Galdhopiggen.

PEER. Where does Harteig lie?

THE CAPTAIN (pointing). About over there.

PEER. I thought so.

THE CAPTAIN. You know where you are, it appears.

PEER. When I left the country, I sailed by here; and the dregs, says the proverb, hang in to the last. (Spits, and gazes at the coast.) In there, where the scaurs and the clefts lie blue,—where the valleys, like trenches, gloom narrow and black, and underneath, skirting the open fiords,—it’s in places like these human beings abide. (Looks at the captain.) They build far apart in this country.

THE CAPTAIN. Ay; few are the dwellings and far between.

PEER. Shall we get in by day-break?

THE CAPTAIN. Thereabouts; if we don’t have too dirty a night altogether.

PEER. It grows thick in the west.

THE CAPTAIN. It does so.

PEER. Stop a bit! You might put me in mind when we make up accounts—I’m inclined, as the phrase goes, to do a good turn to the crew—

THE CAPTAIN. I thank you.

PEER. It won’t be much. I have dug for gold, and lost what I found;—we are quite at loggerheads, Fate and I. You know what I’ve got in safe keeping on board—that’s all I have left;—the rest’s gone to the devil.

THE CAPTAIN. It’s more than enough, though, to make you of weight among people at home here.

PEER. I’ve no relations. There’s no one awaiting the rich old curmudgeon.—Well; that saves you, at least, any scenes on the pier!

THE CAPTAIN. Here comes the storm.

PEER. Well, remember then—If any of your crew are in real need, I won’t look too closely after the money—

THE CAPTAIN. That’s kind. They are most of them ill enough off; they have all got their wives and their children at home. With their wages alone they can scarce make ends meet; but if they come home with some cash to the good, it will be a return not forgot in a hurry.

PEER. What do you say? Have they wives and children? Are they married?

THE CAPTAIN. Married? Ay, every man of them. But the one that is worst off of all is the cook; black famine is ever at home in his house.

PEER. Married? They’ve folks that await them at home? Folks to be glad when they come? Eh?

THE CAPTAIN. Of course, in poor people’s fashion.

PEER. And come they one evening, what then?

THE CAPTAIN. Why, I daresay the goodwife will fetch something good for a treat—

PEER. And a light in the sconce?

THE CAPTAIN. Ay, ay, may be two; and a dram to their supper.

PEER. And there they sit snug! There’s a fire on the hearth! They’ve their children about them! The room’s full of chatter; not one hears another right out to an end, for the joy that is on them—!

THE CAPTAIN. It’s likely enough. So it’s really kind, as you promised just now, to help eke things out.

PEER (thumping the bulwark). I’ll be damned if I do! Do you think I am mad? Would you have me fork out for the sake of a parcel of other folks’ brats? I’ve slaved much too sorely in earning my cash! There’s nobody waiting for old Peer Gynt.

THE CAPTAIN. Well, well; as you please then; your money’s your own.

PEER. Right! Mine it is, and no one else’s. We’ll reckon as soon as your anchor is down! Take my fare, in the cabin, from Panama here. Then brandy all round to the crew. Nothing more. If I give a doit more, slap my jaw for me, Captain.

THE CAPTAIN. I owe you a quittance, and not a thrashing;—but excuse me, the wind’s blowing up to a gale.

(He goes forward. It has fallen dark; lights are lit in the cabin. The sea increases. Fog and thick clouds.)

PEER. To have a whole bevy of youngsters at home;—still to dwell in their minds as a coming delight;—to have others’ thoughts follow you still on your path!—There’s never a soul gives a thought to me.—Lights in the sconces! I’ll put out those lights. I will hit upon something!—I’ll make them all drunk;—not one of the devils shall go sober ashore. They shall all come home drunk to their children and wives! They shall curse; bang the table till it rings again,—they shall scare those that wait for them out of their wits! The goodwife shall scream and rush forth from the house,—clutch her children along! All their joy gone to ruin! (The ship gives a heavy lurch; he staggers and keeps his balance with difficulty.) Why, that was a buffet and no mistake. The sea’s hard at labour, as though it were paid for it;—it’s still itself here on the coasts of the north;—a cross-sea, as wry and wrong-headed as ever— (Listens.) Why, what can those screams be?

THE LOOK-OUT (forward). A wreck a-lee!

THE CAPTAIN (on the main deck, shouts). Helm hard a-starboard! Bring her up to the wind!

THE MATE. Are there men on the wreck?

THE LOOK-OUT. I can just see three!

PEER. Quick! lower the stern boat—

THE CAPTAIN. She’d fill ere she floated.

(Goes forward.)

PEER. Who can think of that now? (To some of the crew.) If you’re men, to the rescue! What the devil, if you should get a bit of a ducking!

THE BOATSWAIN. It’s out of the question in such a sea.

PEER. They are screaming again! There’s a lull in the wind.—Cook, will you risk it? Quick! I will pay—

THE COOK. No, not if you offered me twenty pounds-sterling—

PEER. You hounds! You chicken-hearts! Can you forget these are men that have goodwives and children at home? There they’re sitting and waiting—

THE BOATSWAIN. Well, patience is wholesome.

THE CAPTAIN. Bear away from that sea!

THE MATE. There the wreck turned over!

PEER. All is silent of a sudden—!

THE BOATSWAIN. Were they married, as you think, there are three new-baked widows even now in the world.

(The storm increases. Peer Gynt moves away aft.)

PEER. There is no faith left among men any more,—no Christianity,—well may they say it and write it;—their good deeds are few and their prayers are still fewer, and they pay no respect to the Powers above them.—In a storm like to-night’s, he’s a terror, the Lord is. These beasts should be careful, and think, what’s the truth, that it’s dangerous playing with elephants;—and yet they must openly brave his displeasure! I am no whit to blame; for the sacrifice I can prove I stood ready, my money in hand. But how does it profit me?—What says the proverb? A conscience at ease is a pillow of down. Oh, ay, that is all very well on dry land, but I’m blest if it matters a snuff on board ship, when a decent man’s out on the seas with such riff-raff. At sea one never can be one’s self; one must go with the others from deck to keel; if for boatswain and cook the hour of vengeance should strike, I shall no doubt be swept to the deuce with the rest;—one’s personal welfare is clean set aside;—one counts but as a sausage in slaughtering-time.—My mistake is this: I have been too meek; and I’ve had no thanks for it after all. Were I younger, I think I would shift the saddle, and try how it answered to lord it awhile. There is time enough yet! They shall know in the parish that Peer has come sailing aloft o’er the seas! I’ll get back the farmstead by fair means or foul;—I will build it anew; it shall shine like a palace. But none shall be suffered to enter the hall! They shall stand at the gateway, all twirling their caps;—they shall beg and beseech—that they freely may do; but none gets so much as a farthing of mine. If I’ve had to howl ’neath the lashes of fate, trust me to find folks I can lash in my turn—

THE STRANGE PASSENGER (stands in the darkness at Peer Gynt’s side, and salutes him in friendly fashion). Good evening!

PEER. Good evening! What—? Who are you?

THE PASSENGER. Your fellow-passenger, at your service.

PEER. Indeed? I thought I was the only one.

THE PASSENGER. A mistaken impression, which now is set right.

PEER. But it’s singular that, for the first time to-night, I should see you—

THE PASSENGER. I never come out in the day-time.

PEER. Perhaps you are ill? You’re as white as a sheet—

THE PASSENGER. No, thank you—my health is uncommonly good.

PEER. What a raging storm!

THE PASSENGER. Ay, a blessed one, man!

PEER. A blessed one?

THE PASSENGER. The sea’s running high as houses. Ah, one can feel one’s mouth watering! just think of the wrecks that to-night will be shattered;—and think, too, what corpses will drive ashore!

PEER. Lord save us!

THE PASSENGER. Have ever you seen a man strangled, or hanged,—or drowned?

PEER. This is going too far—!

THE PASSENGER. The corpses all laugh. But their laughter is forced; and the most part are found to have bitten their tongues.

PEER. Hold off from me—!

THE PASSENGER. Only one question pray! If we, for example, should strike on a rock, and sink in the darkness—

PEER. You think there is danger?

THE PASSENGER. I really don’t know what I ought to say. But suppose, now, I float and you go to the bottom—

PEER. Oh, rubbish—

THE PASSENGER. It’s just a hypothesis. But when one is placed with one foot in the grave, one grows soft-hearted and open-handed—

PEER (puts his hand in his pocket). Ho, money!

THE PASSENGER. No, no; but perhaps you would kindly make me a gift of your much-esteemed carcass—?

PEER. This is too much!

THE PASSENGER. No more than your body, you know! To help my researches in science—

PEER. Begone!

THE PASSENGER. But think, my dear sir—the advantage is yours! I’ll have you laid open and brought to the light. What I specially seek is the centre of dreams,—and with critical care I’ll look into your seams—

PEER. Away with you!

THE PASSENGER. Why, my dear sir—a drowned corpse—!

PEER. Blasphemer! You’re goading the rage of the storm! I call it too bad! Here it’s raining and blowing, a terrible sea on, and all sorts of signs of something that’s likely to shorten our days;—and you carry on so as to make it come quicker!

THE PASSENGER. You’re in no mood, I see, to negotiate further; but time, you know, brings with it many a change— (Nods in a friendly fashion.) We’ll meet when you’re sinking, if not before; perhaps I may then find you more in the humour.

(Goes into the cabin.)

PEER. Unpleasant companions these scientists are! With their freethinking ways— (To the boatswain, who is passing.) Hark, a word with you, friend! That passenger? What crazy creature is he?

THE BOATSWAIN. I know of no passenger here but yourself.

PEER. No others? This thing’s getting worse and worse. (To the ship’s boy, who comes out of the cabin.) Who went down the companion just now?

THE BOY. The ship’s dog, sir!

(Passes on.)

THE LOOK-OUT (shouts). Land close ahead!

PEER. Where’s my box? Where’s my trunk? All the baggage on deck!

THE BOATSWAIN. We have more to attend to!

PEER. It was nonsense, captain! ’Twas only my joke;—as sure as I’m here I will help the cook—

THE CAPTAIN. The jib’s blown away!

THE MATE. And there went the foresail!

THE BOATSWAIN (shrieks from forward). Breakers under the bow!

THE CAPTAIN. She will go to shivers!

(The ship strikes. Noise and confusion.)

Act IV Scene 13 |

Act V Scene 2 |